AI in Agrifood: Signals and Reflections from November 2025

AI-powered pesticide discovery advances, whole-genome models accelerate crop breeding, and more.

Hey folks!

Thanks for being here. For Issue #128 of Better Bioeconomy, I’m trying something new. I want to experiment with a monthly edition on AI (artificial intelligence) in agrifood, a format that lets me look across the developments from last month to see where patterns are starting to emerge.

Why this format? Because I increasingly believe that intelligent systems, whether we label them AI, ML (Machine Learning) or automation, can meaningfully accelerate progress in agrifood. The exact terminology is less important for this series. I’m using “AI” here as a practical shorthand for that whole toolkit.

So in this issue, you’ll find a curated round-up of November’s AI x agrifood news, a World Bank/Gates report on AI as agricultural infrastructure, and some of my reflections on where the leverage (and the risk) might be.

This is still an experiment, so I’d love to hear what you think. As always, my understanding keeps evolving as I dig deeper. My goal with this series isn’t to declare an AI revolution or to pretend I’m an AI expert. If you spot something I’ve missed or got wrong, let me know.

Let’s jump in!

AI X AGRIFOOD NEWS

🐛 Bindwell raised $6M to reinvent pesticides using AI

Bindwell is reframing pesticide discovery as an AI-native search problem, adapting drug-discovery models (Foldwell, PLAPT, APPT) to predict protein structures, protein–protein interactions and binding affinities for agricultural targets, enabling rapid in silico exploration of novel modes of action.

The company reports that its structure-prediction system runs ~4x faster than AlphaFold 3, while APPT achieves ~1.7x higher accuracy on a standard affinity benchmark. Taken together, the “scan every known synthesised compound in ~6 hours,” generating a computational funnel that narrows vast libraries to a short list of viable candidates.

Its $6M seed round will fund the shift from benchmarking to wet-lab validation, with Bindwell intending to license IP for new pesticide actives, positioning it as a next-generation agrochemical discovery engine.

Source: TechCrunch

🍫 World’s largest B2B chocolate maker is partnering with NotCo to bring AI into chocolate formulation

Barry Callebaut is integrating NotCo’s Giuseppe AI into its chocolate R&D pipeline, combining the startup’s ingredient-chemistry and sensory-modelling capabilities with the manufacturer’s extensive formulation data to modernise innovation amid cocoa volatility, climate stress and health-driven reformulation pressures.

The AI analyses product recipes and ingredient data to predict flavour, texture, and functional outcomes, and proposes recipes that can reduce cocoa usage, improve nutritional profiles, or meet Nutri-Score frameworks.

By shifting early-stage formulation into computation, the partnership aims to cut trial-and-error cycles, increase hit rates and accelerate product development, supporting a new generation of chocolate that maintains indulgence even as formulations evolve for cost, resilience and health considerations.

Source: Food Ingredients First

♻️ MOA Foodtech’s AI fermentation service turns food waste into sustainable ingredients

MOA Foodtech’s “MOA Box” applies AI-driven bioprocess design to help manufacturers convert starch-rich byproducts into high-value protein ingredients through fermentation, enabling clients to access advanced bioprocess R&D without building internal infrastructure.

Its Albatros platform runs 300+ bioprocess simulations per hour, matching each byproduct stream with the optimal yeast strain and fermentation parameters to identify the most efficient, low-cost, and low-impact route. MOA then executes fermentation, downstream processing, and validation before licensing the turnkey process back to the client.

The company reports biomass with all essential amino acids and a protein digestibility score of 0.9 (on par with soy, egg and beef). It claims the approach can generate up to 17.5x more value from starch byproducts while taking clients from byproduct assessment to a market-ready ingredient in ~6 months.

Source: Green Queen

🌾 Avalo harnesses ‘whole genome AI’ to accelerate crop breeding

Avalo applies “whole genome AI” to crop breeding by analysing entire genomes alongside environmental and field-performance data, allowing its interpretable models to identify multi-gene patterns linked to complex traits like drought tolerance, nutrient efficiency and yield stability.

This AI layer sits within a rapid-evolution platform that creates diverse genetic populations, models their performance computationally and then directs breeders toward the most promising crosses, effectively simulating much of the breeding pipeline in silico before committing to long, resource-intensive field trials.

Avalo says this system can halve breeding timelines for crops as complex as sugarcane and highlights early proof points such as a cotton line requiring zero irrigation and 70% less fertiliser, suggesting the platform can generate more climate-resilient, resource-efficient varieties than conventional breeding pathways.

Source: AgFunder

🐕 Cargill put an AI-powered ‘robot dog’ on the factory floor

Cargill has deployed a Boston Dynamics Spot robot at its Amsterdam oilseed crush plant, where it performs roughly 10,000 autonomous inspections per week, using computer vision, thermal imaging and onboard ML to navigate the facility, detect overheating, leaks and other anomalies, and feed structured insights into plant monitoring systems.

The company says Spot has already identified issues such as an overheated decanter and bearings oscillating between 40°C and 100°C, enabling interventions before equipment failure and unplanned downtime. It reports clear gains in early detection, reliability and safety, with the robot delivering a level of consistency that a human walkaround cannot match.

Rather than treating Spot as a labour substitute, Cargill is retraining staff to design missions and interpret the robot’s data, framing the shift as a move toward predictive, data-informed operations. The pilot remains limited to one European site, but the firm is assessing a broader rollout across its network.

Source: AgFunder

😋 Food System Innovations receives $2M to build an open-source AI model for flavour and texture in alt-proteins

Food System Innovations’ NECTAR program has received a $2M Bezos Earth Fund grant to build an open-source AI model that helps companies design better-tasting sustainable proteins, drawing on work led by Stanford computer science PhD researcher Anna Thomas.

NECTAR has amassed a large dataset pairing consumer sensory responses to alternative proteins with detailed molecular and ingredient data. The AI is being trained to connect molecular structure, flavour, texture, and preference patterns so it can predict which formulations are most likely to succeed before companies commit to costly development cycles.

The project’s stated benefits include enabling CPGs and manufacturers to iterate faster and more cost-effectively in alt protein R&D, improving the likelihood that new products succeed on taste, and supporting emissions reduction by making plant-based and other climate-friendly proteins more competitive with conventional meat “one bite at a time.”

Source: Green Queen

📚 AKA Foods raised $17.2M to launch an AI platform that restructures fragmented R&D into an actionable knowledge base

AKA Studio is a domain-specific AI platform that ingests a food company’s decades of scattered R&D, sensory and regulatory data and restructures it into a unified, searchable “food grammar.” It captures ingredient specs, experimental measurements and sensory attributes like texture, aroma and taste in one coherent knowledge base.

AI assistants and agents sit on top of this foundation, querying internal and external data to recommend formulation improvements or new product concepts, giving R&D teams an intelligent co-pilot that can reason across chemistry, functionality, sensory outcomes and regulatory constraints without acting as an opaque black box.

AKA Foods says this approach can shrink innovation cycles from years to weeks, raise the quality and confidence of R&D decisions, and support the development of cleaner-label, lower-sugar, lower-fat and more resilient formulations, all while ensuring strict data security through private or on-prem deployments where client data never leaves their environment or trains shared models.

Source: FoodBev

🤖 Ceres AI raised $13M to scale an agricultural intelligence platform spanning 32M acres

Ceres AI has raised $13M to scale its “AI for Agricultural Intelligence” platform, which is built on 17 billion plant-level measurements spanning 32 million acres and 40+ crop types. Its models analyse this dataset, turning imagery and plant-level measurements into high-resolution analytics for agribusiness and financial institutions, supporting insurance, lending and other risk-management workflows.

These insights feed into the workflows of agribusinesses, insurers, lenders and farmland investors, where the AI now informs underwriting, loan pricing, risk monitoring, input allocation and portfolio management. The company positions this as an emerging “agricultural intelligence layer” that makes decisions faster, more consistent and more transparent.

Ceres AI claims this infrastructure can improve performance, profitability and climate-risk management for customers. The round also drew attention for the appointment of Arista, an AI agent, as what they describe as the first AI board member.

Source: iGrowNews

AI X AGRIFOOD REPORT

Harnessing AI for agricultural transformation

A World Bank-led report argues that AI is becoming a foundational tool for agricultural transformation, especially in LMICs (Low- and Middle-Income Countries), where climate shocks, rising input costs and weak supply chains threaten food security. It highlights that AI’s value lies in improving productivity, sustainability and inclusion across agrifood systems.

AI is positioned as uniquely suited to agriculture because the sector generates multi-modal, unstructured data, from images and text to climate records and sensor inputs. Generative AI builds on this by enabling localised, conversational advisories that can overcome literacy, language and access barriers for small-scale producers.

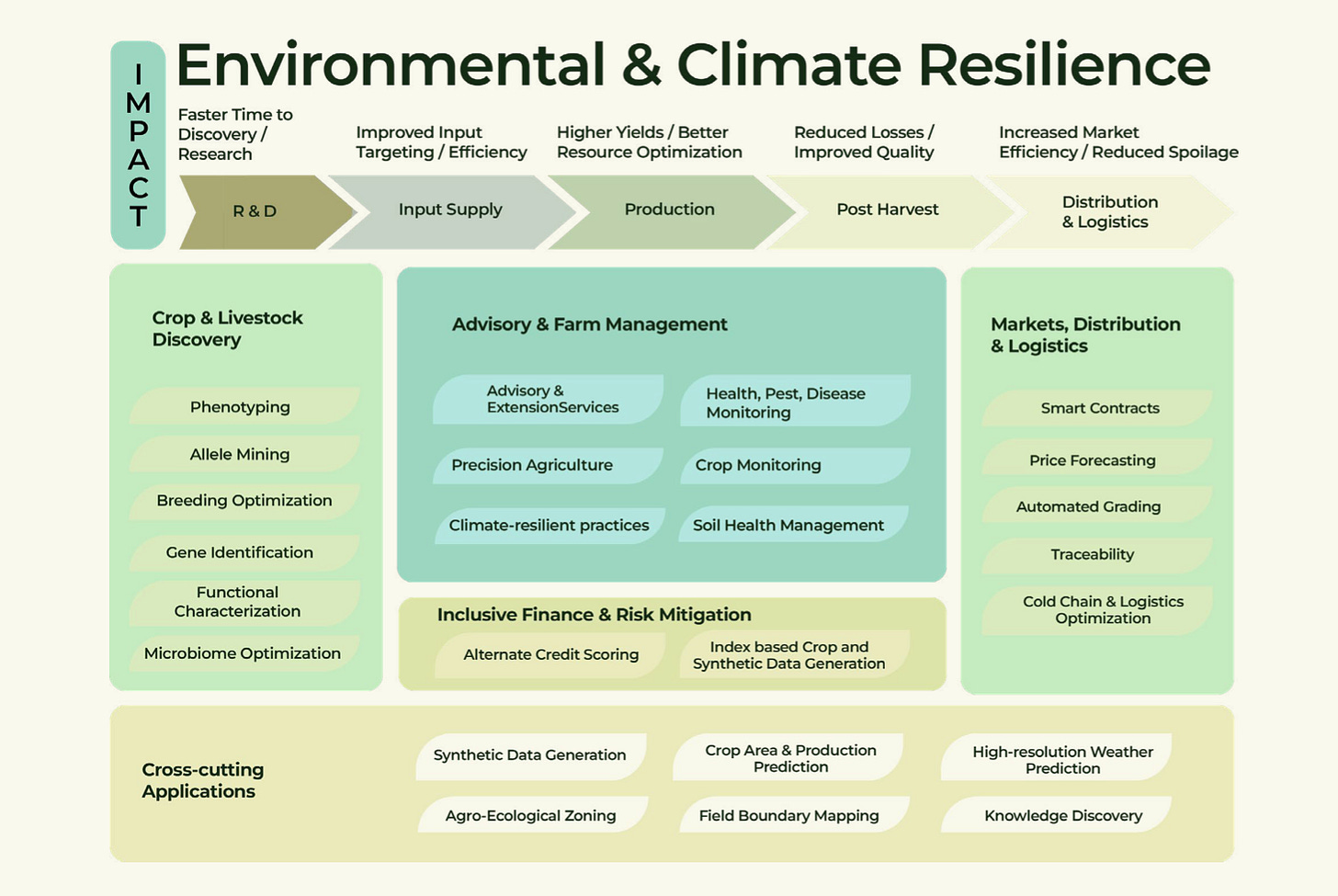

The report also highlights high-impact use cases across the value chain. This includes crop and livestock discovery, AI-powered advisory and farm management, inclusive finance and risk mitigation, market and logistics optimisation, and cross-cutting applications such as satellite-enabled crop forecasting and agro-ecological zoning.

It stresses that AI will only deliver equitable benefits if supported by foundational enablers: robust connectivity and energy infrastructure, localised datasets, digital literacy and human capital, clear data governance, and strong public-private ecosystems. This includes building agricultural Digital Public Infrastructure (DPIs) like farmer registries, data exchanges and open service networks.

The investment priorities of the report focus on agriculture-specific AI models, foundational data systems, compute infrastructure, and policy frameworks that enable responsible scaling. The forward look warns that AI must be guided by inclusion, ethics, and local relevance to avoid reinforcing inequalities while unlocking climate resilience and productivity gains.

Source: World Bank

REFLECTIONS

Emerging patterns

1. AI is becoming a workhorse in discovery

Bindwell, Avalo, MOA Foodtech, the NECTAR project and the Barry Callebaut-NotCo collaboration all point in the same direction: AI is being treated as a viable tool inside discovery workflows. The common thread is that these teams are tackling problems where the search space is too large for human iteration alone – chemical space for pesticides, combinatorial breeding space for complex crops, the huge design space of fermentation conditions or flavour systems.

If platforms like Bindwell move beyond benchmark performance into validated hits, and if Avalo’s cotton result proves reproducible, the front end of the R&D cycle could compress significantly. That still leaves regulatory and manufacturing timelines intact, but it meaningfully shifts which projects become economically viable to pursue.

A notable feature of this wave is how domain-specific the systems are. Bindwell’s models are tuned for agrochemical binding, not generic protein folding. Avalo’s models are wired into specific crops and environments. NECTAR is explicitly built on sensory panels and meat-eater preferences, while NotCo’s Giuseppe is trained on food composition and processing constraints. The leverage comes from combining solid domain data, clear objective functions, and an architecture that respects the constraints of regulation, scale-up and cost.

2. Food companies are turning decades of R&D into an asset

AKA Foods, Symrise and, indirectly, the Barry Callebaut–NotCo deal all highlight another shift: large food companies are starting to treat their messy archives of R&D reports, sensory tests and regulatory dossiers as something that can be structured and queried. AKA’s “food grammar” framing captures this well: the goal is to encode the relationships between ingredients, processes, sensory outcomes and constraints so an AI system can reason with R&D teams rather than hallucinate novelty.

This is less glamorous than “AI chef”, but it lines up with how big organisations typically work. Formulation teams are constrained by past experiments, existing supply contracts, compliance rules and brand guardrails. Systems like AKA Studio are essentially knowledge-operating systems for that reality.

If they work, the payoff is not that AI suddenly “invents” a new category (although that might be possible), but that teams can avoid repeating old mistakes, respond faster to shocks (like cocoa price spikes) and have a clearer map of what is technically possible within their own house.

3. Risk, finance and infrastructure are becoming natural homes for AI

Ceres AI sits firmly inside the story the World Bank report is telling: AI as an “invisible” layer that informs credit, insurance and policy decisions rather than a frontline app. There’s a clear logic to concentrating AI effort where data is already aggregated – across millions of acres, loan books, insurance portfolios – and where small improvements in risk assessment or pricing can move real capital.

The idea of an “agricultural intelligence layer” isn’t entirely new, but the scale of Ceres’ dataset and the willingness of financial institutions to integrate those signals into underwriting and portfolio management are meaningful signals.

The report’s emphasis on Digital Public Infrastructure (farmer registries, data exchanges, payment rails) also underlines how much of AI’s impact in agrifood is going to depend on unglamorous plumbing. Without reasonably clean, linkable data on who farms where, what they grow and which services reach them, even the smartest risk models or advisory bots are constrained. Ceres, Farmdar-type platforms, and public efforts like KIAMIS in Kenya are all, in different ways, pushing toward that “shared infrastructure” picture.

But this also surfaces a real tension. Systems like AKA Studio, Ceres, and emerging DPI initiatives rely on structured, aggregated data, yet their incentives around openness differ. There is a tradeoff between building defensible proprietary datasets (which investors like) and enabling the interoperability that development institutions argue is essential for equitable outcomes.

Investability

Looking at this through an agrifood tech VC lens, a few areas stand out as more attractive (on paper) for me.

First is vertical, data-rich AI platforms with clear buyers and existing data flows e.g. agricultural risk/finance (Ceres) or enterprise R&D co-pilots (AKA, Symrise-like stacks). They benefit from high switching costs once embedded, measurable impact (loss ratios, time-to-formulation), and relatively clear paths to revenue. The risks are concentration (a few big customers), regulatory scrutiny (especially in finance), and dependence on third-party infra (cloud, DPIs).

AI-augmented discovery for inputs and traits (Bindwell, Avalo, MOA) is also interesting. The upside is substantial if they can own IP around new actives or germplasm. The downside is classic deeptech: high technical risk, long validation cycles, regulatory exposure, and capital intensity in the wet-lab and scale-up stages. These look suitable for patient capital with a strong view on regulatory timelines and exit paths (licensing vs own commercialisation).

On a related note, check out insights from my recent chat with Yoni Glickman, Managing Partner at PeakBridge, who shared how AI actually becomes a value-add in food.

If you found value in this newsletter, consider sharing it with a friend who might benefit from it! Or, if someone forwarded this to you, consider subscribing.

Hi Eshan! How are you doing on this wonderful day? Love issue #128 and the AI updates! Thank you for all your do to help educate us with the latest developments in the space. I appreciate you. Have a very nice and peaceful week, and Happy Holidays ❤️

Brilliant synthesis of how AI's reshaping discovery pipelines in agritech. The Bindwell case is particulary striking since it's tackling the pesticide problem at the molecular level, basically turning chemical search into a compute problem. What I find intresting is how this dovetails with broader green chemistry principles, optimizing for both efficacy and enviornmental safety before any wet-lab work begins.