Between Ozempic and Oat Bran: Can Biomimetic GLP-1 Supplements Bridge the Gap?

If they do, what does it mean for the food industry?

Hey folks!

Thanks for being here. In Issue #121 of Better Bioeconomy, I’m digging into an emerging space that has caught my attention because it sits at the biotech × food edge: biomimetic GLP-1 supplements.

I’ll start with a quick GLP-1 101, then use Evolv as a case study to separate what’s verified, what’s claimed, and what’s still plausible, and to map the “three lanes” of the GLP-1 economy and what they mean for food and retail.

As always, my understanding keeps evolving as I dig deeper. If you spot something I’ve missed or got wrong, let me know. Let’s jump in!

A quick tour of GLP-1 and what the drugs do

GLP-1 (glucagon-like peptide-1) is a gut hormone released by L-cells in the small intestine when you eat, especially carbohydrates and fats. It belongs to the incretin family, signals that help the body manage post-meal glucose by increasing insulin at the right time and tempering excess sugar release from the liver.

Alongside GLP-1 is GIP (glucose-dependent insulinotropic peptide), made by K-cells higher up the intestine. Together, they form an incretin system that smooths the rise in blood sugar after meals.

Once released, GLP-1 acts in several places. In the pancreas, it increases insulin only when glucose is elevated and reduces glucagon. In the brain, it engages appetite circuits so people feel fuller longer. In the stomach, it slows emptying, so food leaves more gradually and the post-meal glucose curve flattens. There is also evidence of cardiometabolic benefits, which may help explain why some GLP-1 drugs lower cardiovascular risk.

The catch is that native GLP-1 is fleeting. An enzyme called DPP-4 breaks it down within minutes, so the signal is great for meal-by-meal control but too short for steady appetite regulation over hours or days.

GLP-1 drugs solve this by using receptor agonists (engineered molecules that bind to and activate the same receptor as the natural GLP-1 hormone) but are built to resist DPP-4 and stay active for much longer. Classic agonists like liraglutide, semaglutide, and dulaglutide mimic the natural signal but keep it “on” far longer.

Dual agonists such as tirzepatide activate both GLP-1 and GIP receptors, adding effects on insulin dynamics and fat metabolism. Because these drugs persist, they suppress appetite for most of the day, improve glucose control around the clock, and can drive substantial, sustained weight loss.

The “middle lane” in appetite control

GLP-1 has become mainstream through drugs like Ozempic and Mounjaro that mimic a natural satiety signal and deliver striking weight loss. These drugs work, but they are prescription-only, expensive, and often come with gastrointestinal side effects that make long-term use tricky.

On the other hand, there are familiar nutrition strategies such as more fibre, higher protein, fermented foods, and botanicals. They nudge similar pathways, but the effects are usually modest.

Between those extremes is a widening gap. That space is drawing interest from companies trying to recreate parts of GLP-1 biology with biomimetic GLP-1 supplements designed to fit within dietary-supplement rules rather than drug frameworks.

Evolv positions itself in this “middle lane.” Its flagship product, Evolv GLP-1 Biomimetic, is marketed as a first-of-its-kind oral GLP-1 supplement: a daily yeast-based tablet that aims to reproduce a subset of the appetite-regulating effects seen with injectables.

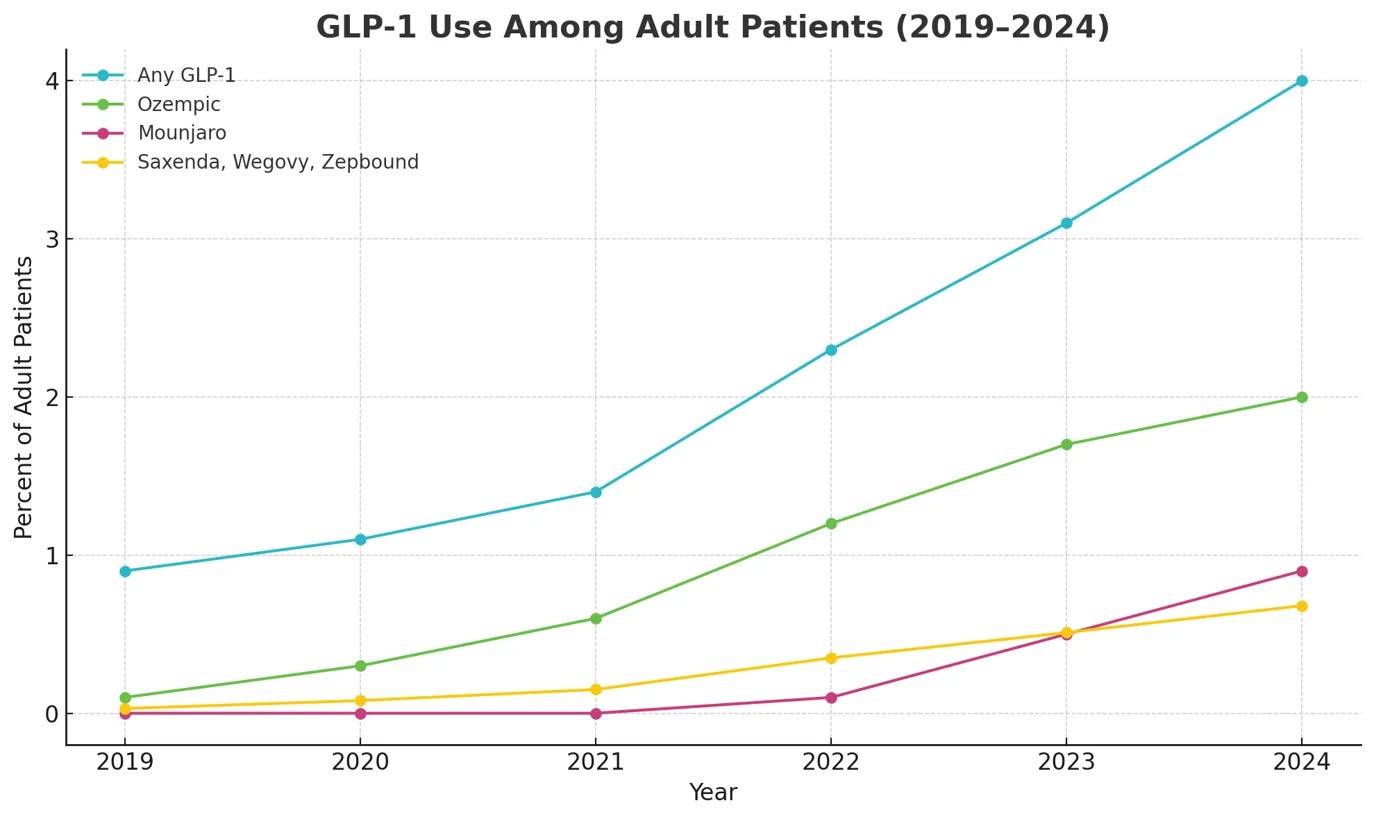

The timing makes sense. Demand for GLP-1 drugs is surging while access and affordability remain constrained, which leaves many would-be users looking elsewhere.

Retailers and supplement brands see an opening, and a grey zone, to offer “GLP-1-like” products over the counter. Regulatory agencies are watching closely but have so far largely “stayed silent” on well-behaved GLP-1 claims, focusing their actions on clear violations (e.g. illegal semaglutide knock-offs or supplements outright claiming to treat obesity). The door is open for science-enabled nutrition companies to step in and prove they can deliver real effects without crossing legal lines.

In this piece, I look at whether biomimetic GLP-1 supplements, using Evolv as a case study, can deliver meaningful, compliant, and affordable appetite support at consumer price points, and what that would mean for the food industry.

Evolv GLP-1 biomimetic snapshot

Evolv GLP-1 Biomimetic is sold direct-to-consumer as a yeast-powered daily supplement “delivering the full power of GLP-1 naturally.” A 30-tablet bottle costs ~$148. Each tablet contains inactivated Saccharomyces cerevisiae (EV1 strain) that the company says carries a proprietary peptide dose inside the yeast biomass.

According to Evolv, EV1 is a new molecule created with AI-guided modelling intended to engage GLP-1 and GIP pathways. The sequence uses canonical amino acids and, per the company, was selected to avoid known drug scaffolds, so it qualifies as a new dietary ingredient.

The company further claims day-long coverage from a design that resists rapid enzymatic breakdown, with an extended activity window described as roughly 24 to 48 hours in preclinical work. The practical promise is once-daily appetite support that sits between transient food signals and the multi-day pharmacokinetics of injectable drugs.

Evolv frames the product as premium but more accessible than prescriptions, at ~$4 per day on subscription. The team highlights a patent-pending peptide and yeast delivery platform, cGMP manufacturing, and third-party testing for identity, purity, and potency. The target user is an adult seeking weight management and metabolic support, especially those who may not access, afford, or tolerate GLP-1 medications.

How does it work?

What happens when you swallow a pill of yeast containing the EV1 peptide? There are two broad possibilities (not mutually exclusive):

Local gut engagement

The peptide may work right in the gut without needing to enter the bloodstream. That’s plausible because GLP-1 sensors are found on cells in the intestinal lining and on nearby nerves that relay “I’m full” messages to the brain. If the peptide is released in the small intestine and reaches those sensors, it can amplify normal post-meal signalling, slowing how quickly the stomach empties. This makes a typical portion feel more satisfying and dials down food noise. Signals from vessels near the gut (the portal area that drains the intestine) may play a role here as well.

In this local model, the peptide functions a bit like certain foods that boost satiety hormones or stimulate gut-to-brain signals. It doesn’t require much absorption into the blood. The upside is that there is less demand for crossing the intestinal barrier. The downside is that the effects might be limited to appetite (and perhaps slower digestion) but not things like insulin release, since to affect blood glucose significantly, a GLP-1 mimic usually needs to reach the pancreas or induce hormones like insulin indirectly.

Systemic absorption and circulation

Evolv clearly designed EV1 with oral bioavailability in mind. They mention engineering stability (to survive stomach acid and enzymes) and transport (to cross the gut lining). If EV1 (or fragments of it) is absorbed into the bloodstream in sufficient amounts, it could then directly engage GLP-1 receptors throughout the body.

However, achieving meaningful systemic levels via oral delivery is very challenging. Typically, peptides the size of GLP-1 (~30 amino acids) have extremely low oral bioavailability unless helped by penetration enhancers or special formulations.

Evolv claims to avoid broad “permeation enhancers” (which can make the gut leaky to all sorts of molecules) and instead uses a “proprietary molecular technology” to specifically get their peptide across the epithelium. This is likely linked to the yeast matrix or a particular fusion design, though details are scarce.

In any case, systemic action would be needed to fully mimic drug-like effects (e.g., lowering blood glucose via insulin or affecting fat storage). It remains to be seen how much of EV1 actually reaches circulation intact.

How do we know if this really works?

The way I like to think about it is an evidence ladder, moving from mechanism to molecules to models to humans:

At the time of writing, there are no peer-reviewed, controlled human data showing weight-loss or metabolic benefits for this product. Evolv appears to have done early, sensible work on a new dietary ingredient, recognising hurdles like DPP-4 breakdown and oral absorption, engineering around them, and assembling safety data for New Dietary Ingredient Notification (NDIN) review. That helps with tolerability and regulatory readiness, but it doesn’t answer efficacy.

What’s public today includes company-run in-vitro assays, animal safety with qualitative appetite signals, and anecdotal user reports of early appetite and weight changes. These are hypothesis-generating, not proof. Without randomised, placebo-controlled trials, we can’t separate any product effect from expectation, concurrent diet changes, or regression to the mean.

Zooming out, this is typical for a new class. Other GLP-1-adjacent entrants are at similar stages: plausible biology, modest early signals, and RCTs in flight. Eg: Lembas has rodent data suggesting reduced intake and weight, and says human studies are coming. Until those data arrive, claims about meaningful, reproducible benefits should be treated as hypotheses.

Supplement or drug?

For a product like Evolv GLP-1, the line between supplement and drug is all about ingredient category and claims.

Under the Dietary Supplement Health and Education Act (DSHEA), a dietary supplement must contain a “dietary ingredient” (such as a vitamin, mineral, herb/botanical, amino acid, or other dietary substances used to supplement the diet). It must also be marketed with structure-function claims rather than disease or drug claims. A novel peptide produced in yeast isn’t a classic vitamin or herb, so Evolv leans on the dietary substance lane and on yeast as the anchor.

On the ingredient side, Evolv says it filed a New Dietary Ingredient Notification (NDIN) with the FDA. NDIN applies to ingredients not marketed in the US before 1994. FDA may issue no objection (the company may market, though this is not “approval”) or object (e.g., safety concerns or incomplete data).

NDIN is different from GRAS (Generally Recognised as Safe), which is usually the route for adding ingredients to conventional foods. My understanding (I’m not a legal expert, so don’t take my word for it) is that if Evolv ever wants EV1 in beverages or bars, a GRAS evaluation/notice would likely be needed.

On claims, Evolv’s consumer copy stays in structure-function territory. They use phrases like “supports satiety,” “helps regulate appetite,” and “supports healthy blood glucose after meals,” paired with the standard disclaimer that the FDA has not evaluated the statements and that the product is not intended to diagnose, treat, cure, or prevent disease.

I notice they avoid explicit disease claims and steer clear of drug-style receptor language on-site. In interviews, they may explain that the peptide engages GLP-1/GIP receptors. Still, web copy leans on “activates GLP-1 pathways” or “mimics the body’s GLP-1”, which reads as supporting normal physiology rather than making a drug claim.

Remember the FTC side of the house too. Advertising must have competent and reliable scientific evidence. The stronger the claim, the stronger the evidence expected.

The three-lane GLP-1 economy

To put biomimetic supplements in context, it’s helpful to compare three broad approaches to tapping the GLP-1 pathway. Lane 1 is endogenous stimulation via diet and nutrients. Lane 2 is biomimetic GLP-1 supplements (eg: yeast-delivered peptides). Lane 3 is pharmaceutical GLP-1 agonists (prescription drugs).

Each lane has a role. Lane 1 is foundational, safe, accessible, and complements any plan, but effects are modest. Lane 2 is the newcomer, aiming for a gentler version of the drug biology in a supplement format. If it delivers even a fraction of Lane 3’s effect at lower cost, it could serve people who aren’t prescription candidates. This lane will live or die by controlled human study evidence. Lane 3 remains the most effective, yet cost, access, and side effects are real constraints, and multi-year safety for broad weight-management use is still being studied.

On behaviour, think complementarity before substitution. Consumers may start with Lane 1 changes, then graduate to Lane 2 supplements if they need an extra push, and only consider Lane 3 drugs if those don’t suffice. Some might combine approaches with medical guidance, for example, pairing a GLP-1 drug with fibre. Combining a GLP-1 drug with a GLP-1-like supplement could compound side effects, so caution is warranted.

On industry dynamics, food companies in Lane 1 are exploring Lane 2 ingredients to counter the demand shift created by Lane 3. This quote by Gil Horsky, founding chairman of Lembas, is summed up as follows: “Right now, the pharma industry is literally eating the lunch of the big food companies. First, by making people eat less, and second, by reaping billions out of these drugs. So if you can’t beat them, join them.” If satiety peptides can be embedded into foods and beverages, the boundary between lanes blurs.

What could this mean for the food sector?

Let’s imagine that these biomimetic GLP-1 supplements do pan out as legitimately helpful tools (say, enabling a 5% weight loss with good safety). What ripple effects could that have across sectors?

1. From nutrients to “smart satiety” in product design

If biomimetics work, CPG formulation moves beyond adding bulk or protein toward purpose-built satiety signals. The job becomes delivering a tiny dose through processing and early digestion so it can nudge appetite pathways. Expect microencapsulation, pH-triggered release, and pairing with protein or viscous fibres.

Early placements land in shakes, bars, and shots where flavour and texture are easier to control, then migrate into broader formats as stability, bitterness masking, and label-friendly carriers improve. This only sticks if teams meet taste and stability specs at commercial COGS and demonstrate batch-to-batch potency.

2. A new retail “metabolic wellness” lane and higher consumer expectations

Labels move from “high protein” and “good source of fibre” to “supports satiety,” with on-pack summaries and QR links to readable study briefs. Merchandising clusters these products between supplements and better-for-you snacks, guided by cues like “helps you feel satisfied on fewer calories.”

Consumers start comparing satiety per serving, not just calories per serving, which raises the bar for proof and consistency. Retailers will ask for clean structure-function copy, NDIN or GRAS clarity, and at least one controlled study before authorising dedicated space.

3. The supplement aisle gets an evidence upgrade

If biomimetics gain traction, they will displace jittery “fat burners” and vague blends. Attention will shift toward single-mechanism, assayable ingredients with NDIN filings, identity specs, stability data, and at least one controlled trial.

Scrutiny increases in a good way: tighter guardrails on claims, stronger post-market QA, and fewer “proprietary blends” that promise too much. Copycats will try to borrow the language without the data. Brands that publish methods, dose specifications, and third-party results will separate quickly from hype.

4. Biotech-big food partnerships reshape the supply chain

Expect tie-ups between peptide startups and global food or ingredient companies. Precision-fermentation capacity, microcapsule fillers, and contract QA labs become new nodes in the food supply chain.

You get a hybrid class that isn’t a drug and isn’t just conventional food: co-branded products with pharma-lite controls, clinician/dietitian input, and placement near protein/fibre rather than multivitamins.

Over time, large brands may standardise satiety specs the way they once standardised protein grams. Partnerships scale only if IP and freedom to operate are clean, regulatory timing for Novel Food or NDI is predictable, and the dose per serving fits typical portions.

Final thoughts

The need for a middle lane is real. The gap between diet-only tools and prescription GLP-1 drugs isn’t going away. The science behind biomimetic GLP-1 supplements is promising, but this category will live or die by evidence, not enthusiasm. Near term, the bar is a pre-registered, well-controlled human study showing measurable benefit versus placebo, with aligned appetite/glycemic signals and clean tolerability.

If that’s met at a cost-competitive price with compliant claims and basic QA (clear identity, consistent potency, stable shelf life), a credible middle lane can emerge. If not, the centre of gravity stays with drugs and diet fundamentals. For operators, the playbook is discipline: design to that bar, publish methods and batch data, and keep claims strictly in structure-function territory.

If you found value in this newsletter, consider sharing it with a friend who might benefit from it! Or, if someone forwarded this to you, consider subscribing.

Hi Eshan, how are you doing on this wonderful day? Love issue #121! Wow! I learned more about GLP-1 from this great newsletter than I ever knew before. Thanks for providing detailed information on how GLP-1 works, and how Evolv is using modified yeast to sort of mimic the benefits of GLP-1 products. I liked your clever use of graphics in #121. I've read some good progress reports from people taking GLP-1, and I've read some horror stories some people report that the body gets tolerant to GLP-1 over time, and how it can negatively affect moods. I exercise daily, I'm vegetarian, and I watch my weight so I don't use GLP-1 products. But I'm glad to see a bio version on the market for people who might benefit from bio GLP-1. The community appreciates all your hard work and efforts Eshan in helping keep us updated on some important and fascinating developments in the space. Have a very nice and peaceful week my friend. I appreciate you 👍❤️