VC Math in Agrifood Tech: What It Takes to Return the Fund

How ownership, dilution, and exits shape fund returns through an agrifood lens.

Hey folks!

Thanks for being here. In Issue #117 of Better Bioeconomy, I want to unpack a phrase VC fund managers often use: “Will this deal return our fund?”

It’s a simple question with big implications. In this piece, I break down what it means by grounding the math in agrifood realities like lumpier capital raises, exits that cluster in the low hundreds of millions, and longer evidence cycles.

The aim is to demystify the numbers for venture capital, a type of capital that has been central to agrifood tech’s growth, so you can better understand the logic driving valuations, ownership negotiations, and follow-on decisions.

Quick disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed in this newsletter are my own and do not necessarily reflect those of my employer, affiliates, or any organisations I am associated with.

As always, my understanding keeps evolving as I dig deeper. If you spot something I’ve missed or got wrong, let me know. Let’s jump in!

“Will this deal return our fund?”

This is a question venture investors keep top of mind when evaluating opportunities. For a venture capital (VC) fund, that’s shorthand for: if this startup succeeds, could it generate enough money to cover the entire fund size we are investing from? In other words, could one company realistically “pay back” the fund on its own?

Since VC is a hits-driven business where a few outliers drive most of the returns, investors use this as an early filter rather than a rule that every deal must meet. Many fund managers target about 3-4x on invested capital over a standard 10-year fund life.

In software, that logic can hide behind smooth growth curves and scalable unit economics. In agrifood, the same question feels sharper. Exits in this space tend to cluster in the low hundreds of millions rather than billions, capital arrives in lumpier tranches tied to trials and facilities, and regulatory or evidence hurdles can stretch timelines.

Understanding this math explains why VCs chase certain outcomes, push for specific ownership levels, haggle over valuations, and sometimes pass on promising businesses, even those solving real food-system challenges.

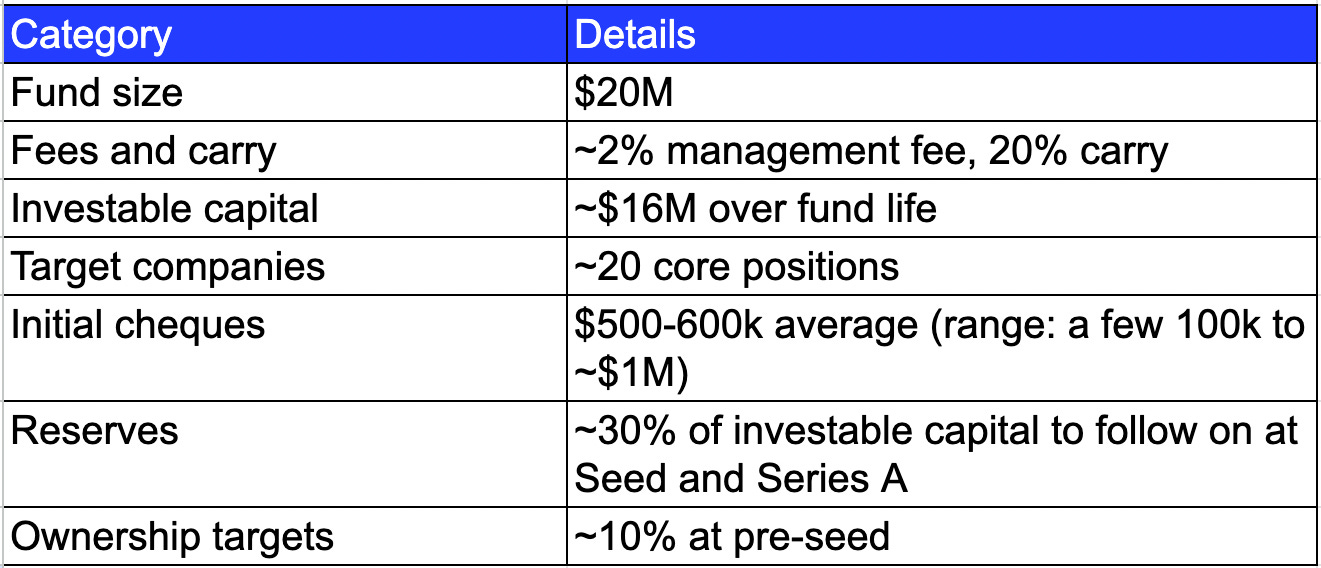

Meet Better Bioeconomy Capital (BBC): a $20M early-stage agrifood fund

To make the math tangible, meet a fictional fund: Better Bioeconomy Capital (BBC). Think of BBC as a $20M pre-seed vehicle that invests in agrifood tech startups. Like most venture funds, it runs on a “2 and 20” model: 2% annual management fee, 20% carry.

The management fee keeps the lights on. It pays salaries, office costs, and the team that sources and supports startups. Carry (short for carried interest) is the performance-based upside. If the fund makes profits, the managers keep 20% of those gains, with the rest going back to investors.

Over a ten-year life, that 2% fee adds up to roughly $4M, leaving about $16M of capital to put to work.

BBC at a glance

A fund this size cannot write $2-5M first cheques across dozens of companies the way a $500M generalist fund might. It has to be selective: roughly 20 initial bets, with about 30% of capital allocated to follow the strongest performers. A $600k entry could buy 8-12% at pre-seed.

For BBC to achieve its goal of returning 3-4x capital over its life (~$60-80M back to investors on a $20M fund), at least one or two of those positions need to become fund-returners, with others contributing smaller outcomes or going to zero.

Meet AgroLugia

Now let’s see how these fund mechanics play out in practice. Imagine BBC writes its first cheque into AgroLugia (the name has nothing to do with my favourite Pokémon 🙂), a fictional microbial biofertiliser startup engineering field-robust bacteria to improve nitrogen efficiency and soil health.

If BBC owns ~6-10% of AgroLugia at exit, returning a $20M fund typically requires an outcome in the ~$200-330M band. We will look at outcome scenarios in more detail later.

BBC’s ownership changes as AgroLugia grows. Each technical or commercial milestone also becomes a capital gate. From greenhouse validation to multi-site field trials, from pilot fermentation to first commercial batches, each step likely requires a new round of financing.

With every raise, the cap table shifts and ownership dilutes. The question “can this return the fund?” does not go away after the first cheque. It is revisited at each gate as ownership, valuation, and exit pathways evolve.

Ownership and dilution

Every financing decision ultimately shows up in the cap table. At its simplest, the way investors think about outcomes can be reduced to a rough equation:

Ownership × Exit Value = Return

This is a simplification that ignores fees, carry, liquidation preferences, and secondary vs primary mechanics, but it captures the intuition investors use when scanning outcomes.

In practice, “return” is usually judged in DPI (Distributions to Paid-In capital), which is the actual cash that makes its way back to a fund’s investors. Mark-ups on private rounds (TVPI) look impressive on paper, but until an acquisition or IPO converts into cash proceeds, they remain unrealised. This distinction matters because deal structure and exit pathways often decide whether a headline valuation translates into real distributions.

That is why ownership at entry matters so much. It is the lever that connects exit values to eventual cash back to investors. Pre-seed leads often aim for roughly 10-15% ownership while seed leads often push into the high-teens to ~20%.

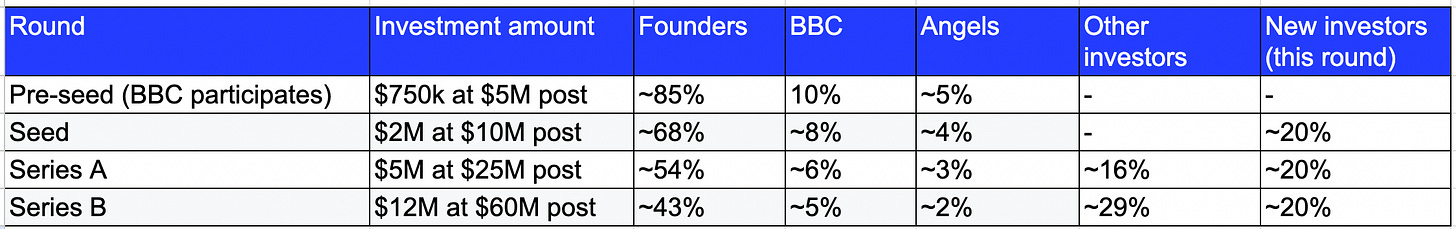

Below is AgroLugia’s dilution path with BBC not following on after pre-seed. New shares are issued each round, so earlier holders shrink as a percentage of the company:

BBC started with a nice 10% stake at pre-seed, but by the time AgroLugia reached Series B, that position had been diluted to about 5%. In a sector where most exits clear in the hundreds of millions, those percentage points matter significantly for whether an investment can plausibly return the fund.

Where agrifood‑specific dilution creeps in

1. Manufacturing scale-up

Scaling from 10-50 L bench runs to 1-5 kL pilots and then 10-30 kL commercial batches requires serious CAPEX: fermenters, downstream separation and filtration, in-line QC, environmental controls, and stability systems.

Process economics depends on volumetric productivity, downstream recovery, and batch success rates. Each transition requires validation campaigns and new SOPs, which are financed in discrete equity rounds that dilute the cap table.

2. Evidence, regulation, and agronomic variability

Generating credible data in agrifood is slower and more expensive than in most tech categories. Agronomic performance must be demonstrated across crops, geographies, and seasons, with statistically robust multi-year, multi-location trial designs and often third-party verification.

Biology doesn’t sprint like software. One bad season or weather anomaly can push pivotal readouts back by 6-12 months, stretching timelines and requiring larger round sizes. Regulatory dossiers then require multi-year data packages and, depending on classification, toxicology or ecotoxicology studies. Grants and non-dilutive funding rarely close the gap, so equity fills it, pushing dilution higher.

3. Commercialisation: inventory and channel build-out

Even when COGS look attractive on paper, early sales seasons are cash-hungry. Inventory must be produced months ahead of revenue, while distributors negotiate long payment terms. This creates a working-capital trough, where companies front-load production and wait on cash collection.

At the same time, “winning the acre” requires on-farm agronomy support, demo plots, field teams, and channel training. These are costs that arrive before scale revenues. Venture debt could offset part of the trough, but restrictive covenants and collateral limits could cap its usefulness. Equity usually shoulders the remainder, adding another dilution notch.

4. Claims and market expansion

Freedom-to-operate, strain deposition, and patent claim breadth shape both defensibility and addressable market. Expanding to new crops or jurisdictions demands incremental data packages, new fieldwork, and additional regulatory submissions. These expansions are critical growth levers, but they also pull spend forward.

Exit pathways in agrifood tech

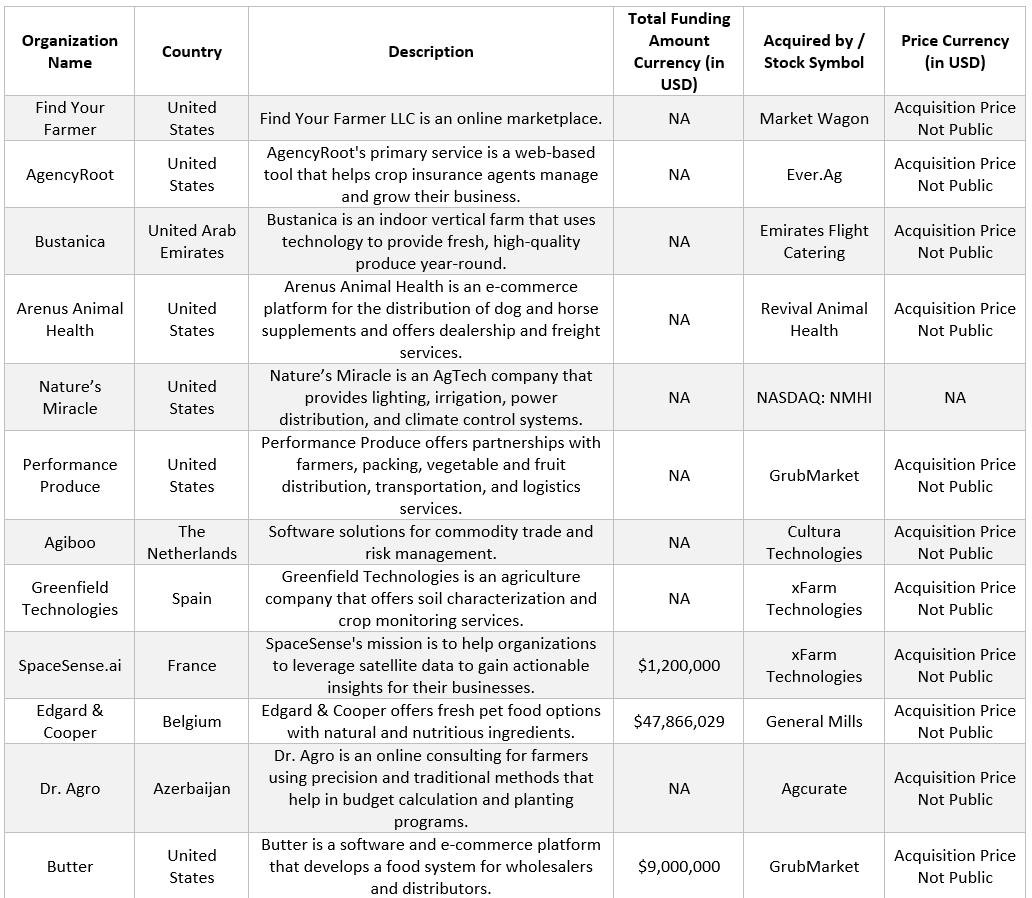

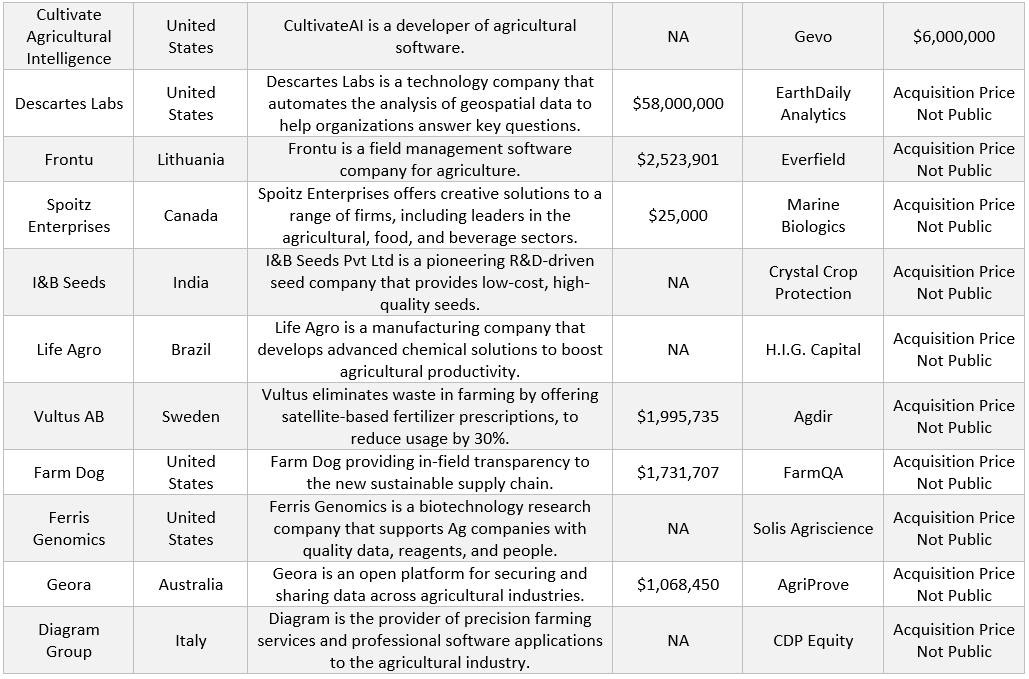

These ownership dynamics only make sense against the reality of exits. In agrifood tech, exits are mostly acquisitions, with IPOs appearing rarely. In 2023, there were 28 agtech exits, all M&A. In 2024, there were 37 exits, 36 M&A and one IPO. That is a clear signal that trade sales, not public listings, are the base case for venture-backed agtech outcomes.

Within those 2024 deals, 34 distinct acquirers showed up. About 47% were other startups or early‑stage companies, 44% were established corporates, and 9% were investment firms or holdcos.

This acquirer mix matters for the VC fund’s outcomes. Different acquirer types bring different consideration structures. Startup-to-startup M&A is often stock-heavy, corporates have more capacity for cash, and investment firms or holdcos may use mixed instruments. For founders and investors, this means that “exit value” and “cash returned” are not always the same.

Looking across nearly two decades of agtech exits (analysis shared by Michael Lee of Syngenta Group Venture), one empirical cut of disclosed deals shows an average value of about $144M across the dataset and a median of about $400M among the top ten exits. In other words, most realisations sit in the low to mid hundreds of millions, with rarer outliers above that.

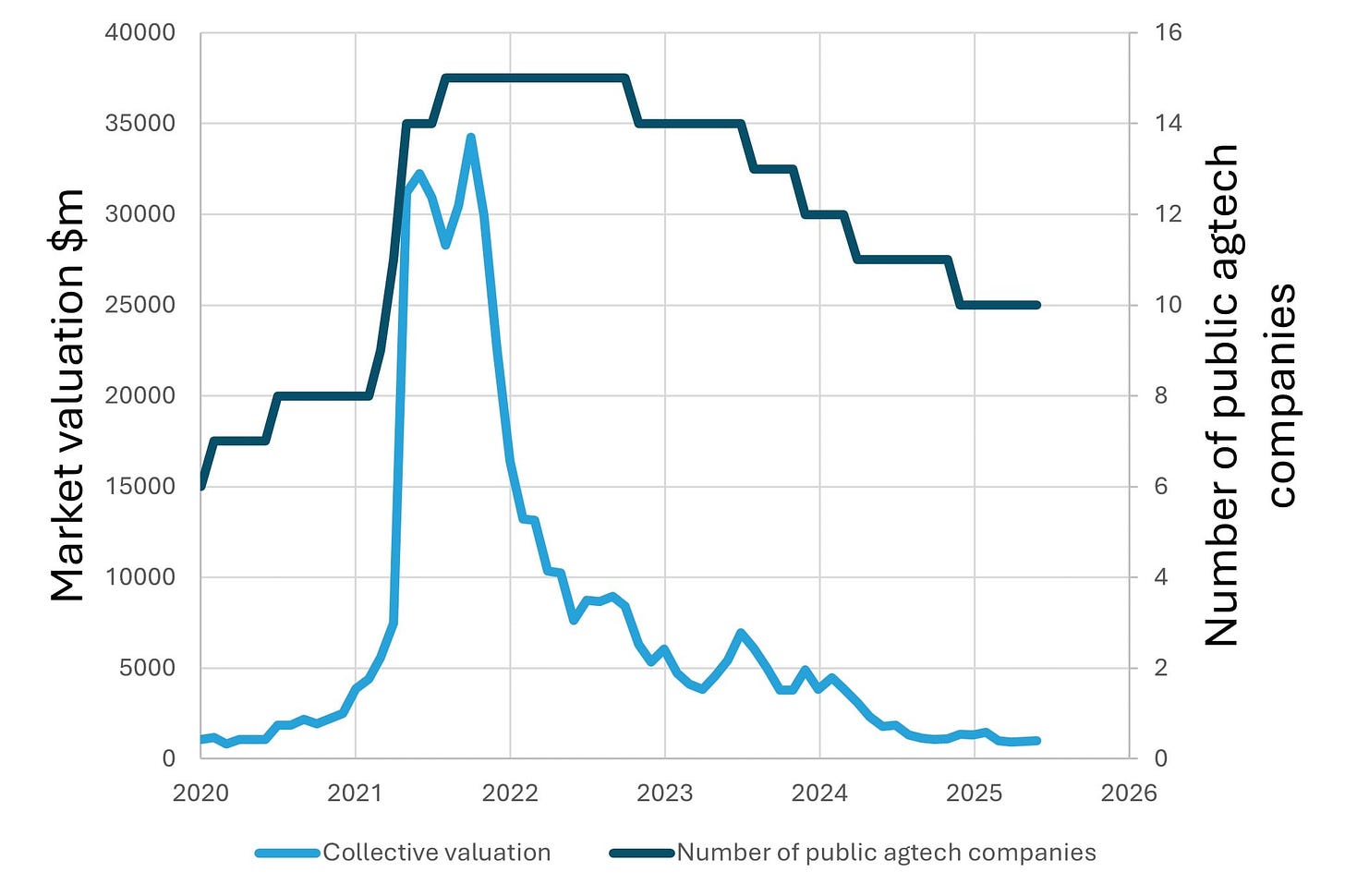

Public markets have been an unreliable path for agtech. One analysis counts an IPO rate of roughly 0.5 companies per year from 2004-2019. There was a brief SPAC-driven bump in 2019-2022, and none since, alongside a sharp deflation in listed agtech valuations from a peak of ~$34 billion in 2021 to ~$1 billion by mid‑2025.

Strategics and OEMs dominate the buyer set. Deere has paid nine-figure sums for autonomy and imagery capabilities, acquiring Blue River for about $305 million and Sentera for an undisclosed amount. DuPont bought Granular for around $250 million to integrate digital agronomy. Syngenta continues to roll up biological inputs such as Intrinsyx Bio. While values are not always disclosed, the pattern is clear: established strategics consolidate tools, platforms, and data that fit their existing portfolios.

The key takeaway here is to plan for M&A as the base case, with corporate strategics and OEMs as the most likely buyers, and underwrite outcomes in the low-to-mid hundreds of millions unless there is a credible line of sight to a different buyer universe or public-market window.

Will the deal return the fund?

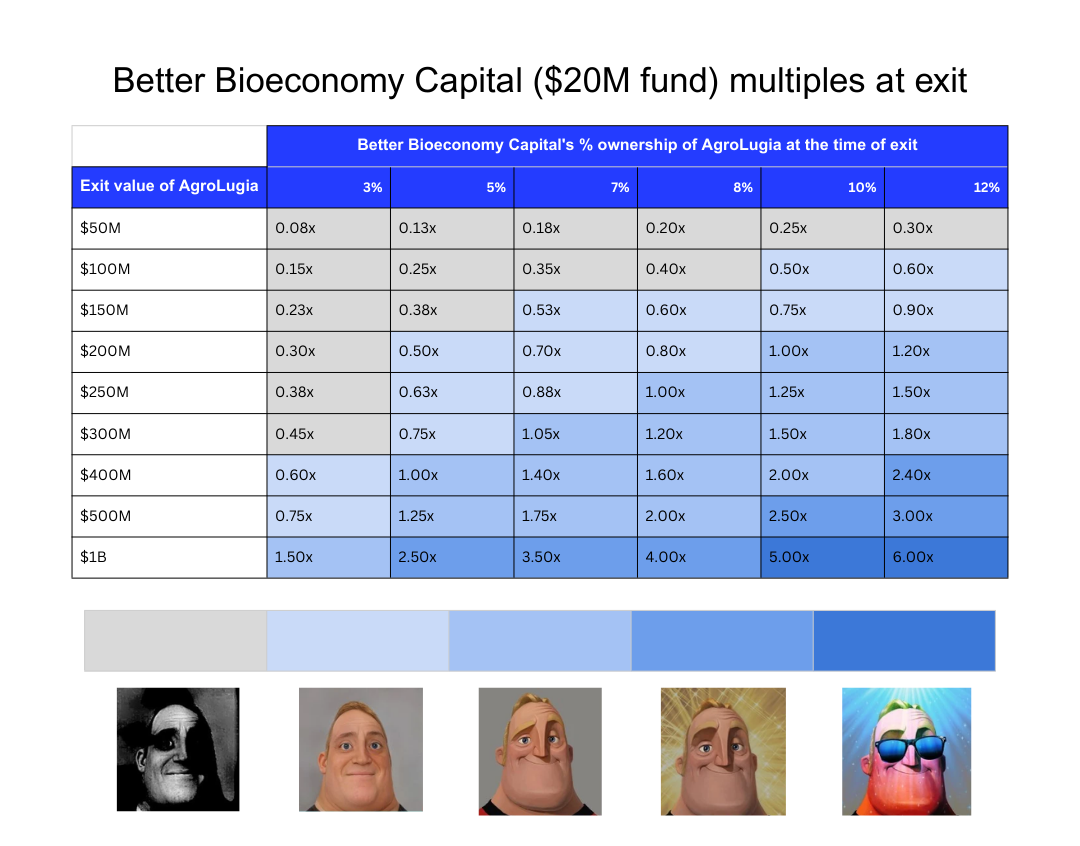

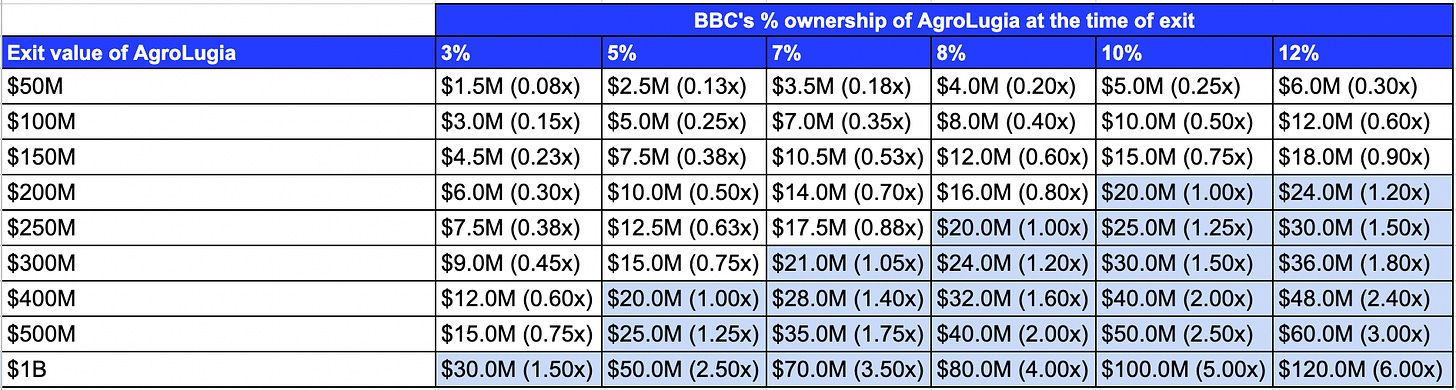

Given everything we have covered so far, let’s see how it plays out for BBC and AgroLugia. The table below shows what BBC would receive at different exit values and ownership levels, and what that translates to against a $20M fund on a gross basis. It turns the “ownership × exit value” idea into concrete numbers:

Given a $20M fund, the numbers show why ownership at exit is a primary driver of outcomes. At the low end, a $50-100M sale rarely moves the needle for the fund. Even at 10%, $100M returns $10M, which is only half the fund on a gross basis.

Good companies can still land here, especially in capital-intensive categories where timelines stretch or markets narrow. Founders may see meaningful outcomes, but the fund math remains underwhelming.

The picture improves in the $200-300M band. At 10%, $200M returns the fund. If BBC drifted to ~7% ownership, $300M still clears a full return, and at 5%, a $300M outcome gets you three-quarters of the way there. This is the zone most micro-funds try to underwrite because one win at these levels can validate a thesis and buy patience for the rest of the portfolio.

Above $300M, the leverage becomes obvious. At 10%, $300M is 1.5x on the fund, and $400M is 2x. Defending early ownership by allocating reserves (30% in BBC’s case, typically concentrated at Series A) is what turns a solid trade sale into a fund-maker.

At 10%, $1B is 5x on the fund, a life-changing result for the fund (and everyone involved). Most exits do not look like that, which is why investors model to the low-to-mid hundreds of millions and focus on preserving the few percentage points that decide whether a deal can plausibly return the fund.

Final thoughts

This piece examined “return-the-fund” math by grounding ownership, dilution, and exits in agrifood realities. One important dimension we only touched lightly is time. Outcomes that look identical in dollar terms can produce very different results once you consider timing and distributions.

A quick primer: The internal rate of return (IRR) is the annualised return a fund delivers to its investors. It depends on when cash goes back, not just how much. For illustration (gross and simplified):

1.0× in 6 years is ~0% IRR, the money just came back

1.5× in 6 years is ~7% IRR

2.0× in 6 years is ~12% IRR

5.0× in 8 years is ~23% IRR

Agrifood exits usually take longer than SaaS because biology and regulation move on seasonal and multi-year cadences. That reality is one reason there is more debate today about whether classic VC is the right fit for agrifood tech companies. It is an important conversation, but one for another time.

If you found value in this newsletter, consider sharing it with a friend who might benefit from it! Or, if someone forwarded this to you, consider subscribing.

Hi Eshan! How are you doing on this wonderful day? Thank you very much for awesome eye opening issue #117. You have considerable knowledge about financing! You could be a VP at Fidelity! I know nothing about investing in startup agriculture businesses. I wish I knew more so I could invest with confidence. I learned a lot from excellent #117 such as the 2% and 20% general rule, lenghts of time managers look to exit their positions, and share dilution. I must admit a lot of this interesting information went over my head. I admire your many skill sets! Thanks for taking the considerable time and effort to help educate us. Keep up the outstanding job. No acts of kindness go wasted. Have a very nice and peaceful week by friend 👍❤️

Thanks for demystifying the investment part, Eshan. I can confirm that the regulatory part is primarily responsible for market entry delays, pricing, and more.