Agrifood Returns Are Low, but the Winners Keep Winning

Here’s what they do differently.

Hey folks,

Happy New Year! I hope 2026 treats you well, that your crops grow strong, your microbes grow fast, and that fundraising, if you’re in the middle of it, goes well.

For Issue #131 of Better Bioeconomy, I’m digging into two recent sources I read over the holidays, one from McKinsey and one from BCG. Both look at a question I think about: why have publicly traded agrifood companies delivered relatively low returns, and what do the consistent winners do differently?

What follows is my attempt to stitch these two reports together: McKinsey’s long-run diagnosis and “big moves,” and BCG’s five-year stress test of what created value from 2020 to 2024.

Let’s dig in! 🍽️

Agrifood is one of those sectors that seem “obviously investable.”

People have to eat. Demand grows with population and income. And when you zoom out far enough, the world is running a multi-decade experiment in reengineering how we produce calories, protein, and inputs under tighter constraints: land, water, labour, and carbon.

However, in public markets, agrifood has not been a consistent creator of shareholder value.

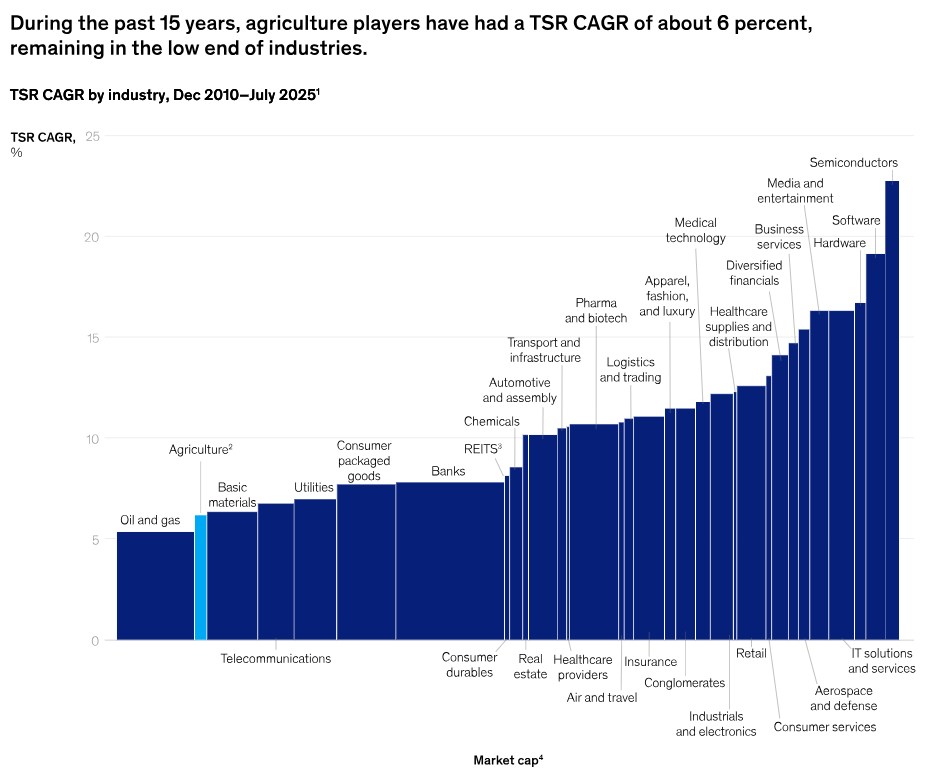

McKinsey’s analysis of 134 publicly traded agrifood companies finds that agriculture delivered an average TSR (Total Shareholder Returns) CAGR of about 6% from 2010 to 2025, trailing the S&P 500 since 2010. TSR is the total return an investor earns from owning a stock: share price gains plus dividends. CAGR (Compound Annual Growth Rate) means the average annual rate over a period.

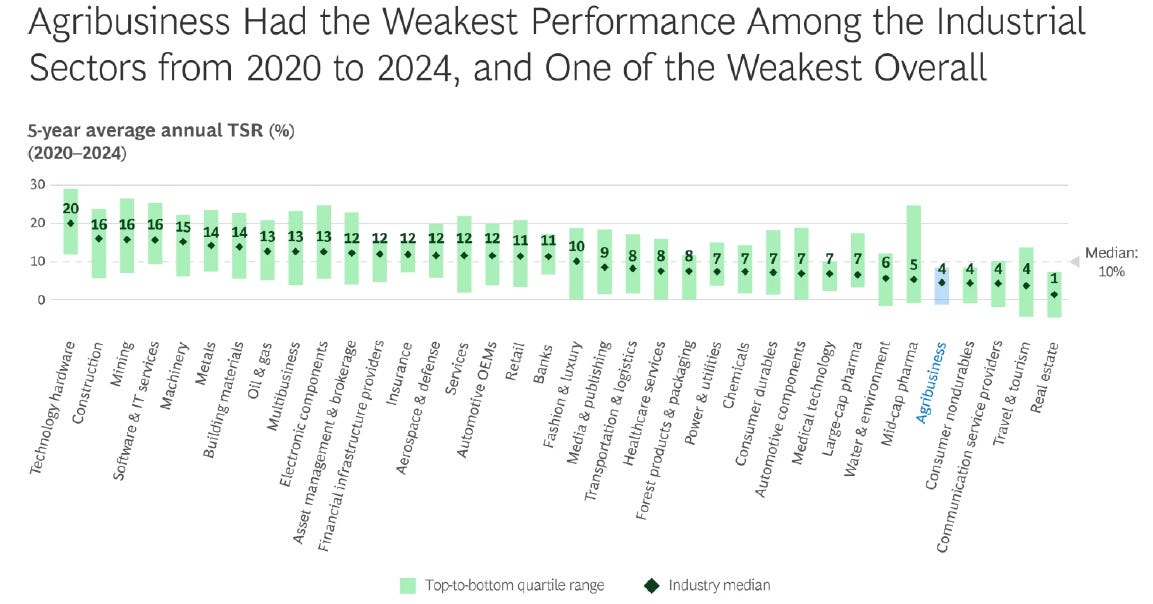

BCG (Boston Consulting Group)’s 2025 Agribusiness Value Creators report reaches a similar conclusion. Among 38 publicly traded agribusiness companies, the median TSR from 2020 to 2024 was 4%, and agribusiness ranked near the bottom of BCG’s sector set, beating only 4 of 36.

Both reports land on the same idea. Agrifood is cyclical, but cycles do not fully explain weak returns. A small group has managed to outperform again and again. The gap comes down to a few practical things: how leaders invest capital, how tightly they manage cash tied up in the business, how well they defend margins, and whether they sell something customers will pay more for.

In other words, the winners are not “riding the commodity cycle.” They are running a different operating system.

What the McKinsey report says

McKinsey frames agriculture’s performance problem as structural.

Volatility is part of the job. Over the past 15 years, agriculture has moved through several distinct phases: a biofuels-driven expansion (2009 to 2013), a return to trend (2013 to 2019), an inflation reset (2019 to 2022), and another return to trend (2022 to 2025).

The bigger issue is that many agrifood companies have not turned that volatility into durable value. McKinsey points to a few recurring drags.

1. Innovation intensity has weakened

Agrifood often underinvests in innovation relative to the complexity of the problems it faces. Median R&D spend has been flat at about 1% of revenue since 2010. Adjusting for inflation, real R&D investment has contracted over time.

In many subsectors, innovation is how you stand out (differentiate). Standing out helps you protect margins. Healthy margins give you room to invest during downturns.

A low-R&D loop tends to create a self-reinforcing trap: underinvest, compete more on price, see weaker margins, then underinvest again.

2. Digital adoption is uneven and often fails to translate into productivity

Digital tools have spread, but not evenly, and not always with the productivity gains people hoped for.

In a 2024 McKinsey survey, about half of US farmers reported using precision agriculture hardware. Adoption was around 30% in Brazil and the EU, and around 5% in India. Adoption of remote sensing, farm management software, and automation was lower.

This matters for two reasons. First, it limits near-term productivity gains across the system. Second, it means many companies are selling tools into markets where adoption is slow and willingness to pay is limited. The value has to be specific and proven.

3. Capital productivity has gotten worse

Agrifood is asset-heavy. It runs on infrastructure, equipment, storage, processing capacity, and distribution networks.

In asset-heavy businesses, small changes in how well assets are used can swing results. McKinsey notes that fixed capital is large relative to the value of goods produced, and fixed asset turns have not improved much since 2010.

4. Working capital has become a drag

McKinsey estimates the sector’s median cash conversion cycle has lengthened by more than 32 days since 2010. The cash conversion cycle is how long cash is tied up after you pay suppliers: you buy inputs, hold inventory, sell, then wait to get paid.

Inventory turnover (how quickly inventory gets sold and replaced) has also dropped. Together, this has pushed the sector to carry more than $60 billion in additional working capital versus 2010.

Working capital (cash tied up in day-to-day operations, mainly inventory and unpaid customer invoices) often looks like accounting. In cyclical industries, it acts like strategy. When too much cash is stuck in inventory and unpaid invoices, you lose flexibility. And flexibility matters most in downturns, when assets and capabilities get cheaper.

What winners do differently

Despite volatility in commodity prices, the common link among leaders is superior ROIC (Return on Invested Capital), driven by greater capital efficiency. ROIC is a measure of how much profit a company generates for each dollar it invests in the business (factories, equipment, inventory, acquisitions). Capital efficiency is about getting more output and profit from the same set of assets, while keeping less cash stuck in inventory.

McKinsey gives examples across four subsectors:

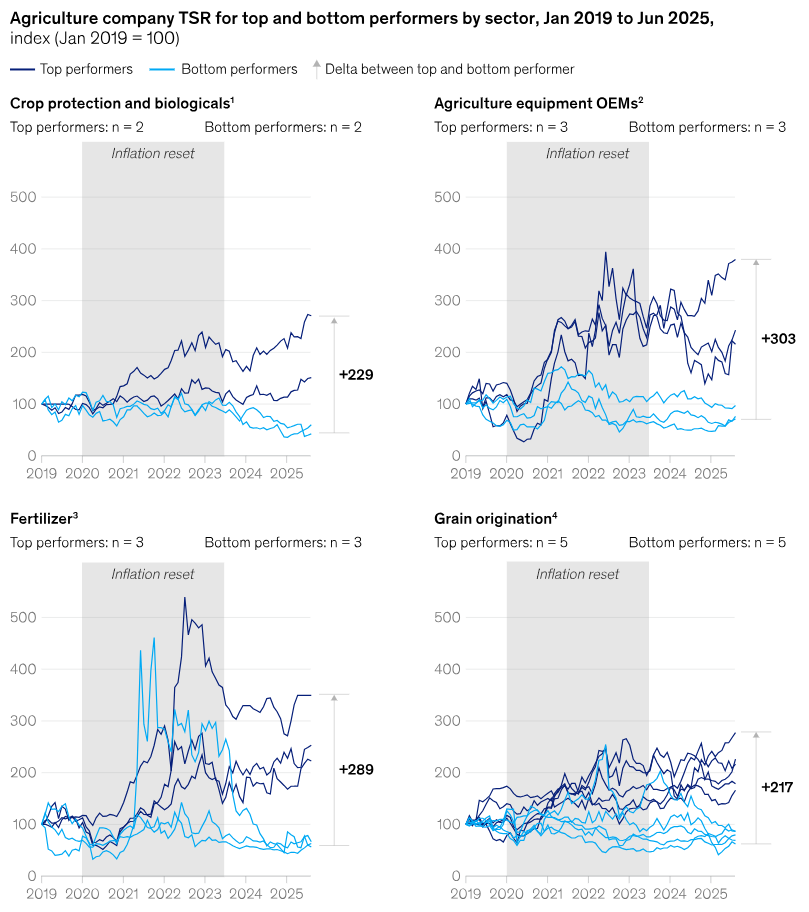

Crop protection and biologicals leaders narrowed offerings toward IP-rich (patents, proprietary formulations, protected traits) segments (patent-protected or proprietary blends), shifted fixed costs to variable costs (including contract manufacturing), and tightened channels and trade spend.

Equipment OEM (original equipment manufacturer) leaders moved to build-to-demand models, reassessed dealers based on inventory and performance, and developed software-enhanced machines priced for farmer outcomes.

Fertiliser leaders reduced conversion costs, offered premium products (multinutrient blends, micronutrients with field-proven nutrient-use efficiency claims), and exited assets requiring sustained heavy CAPEX (large-scale long-term spending such as building plants, buying equipment, or expanding capacity).

Grain origination leaders increased capital turns, consolidated underutilised sites, rebalanced toward advantaged logistics corridors, built digital grower platforms to lower cost to serve, and decommodified outputs (traceable ingredients, lower-carbon-intensity options).

The five “big moves” that show up among outperformers

1. Programmatic M&A

This is not “do a big deal once in a while.” It’s building a repeatable machine for finding deals, evaluating them, integrating them, and learning from them.

McKinsey finds that for leading players, no single deal exceeds 30% of the company’s market value, while total deals add up to about 60% of market value over a decade.

The logic is risk control. One giant acquisition depends on timing and integration going perfectly. A steady cadence spreads risk and builds skill. It also lets companies buy capabilities when prices are lower.

2. Dynamic resource reallocation

Most companies say they allocate capital rationally. Many do not. In practice, many allocate capital by protecting legacy footprints, defending historical priorities, and avoiding politically painful exits.

McKinsey claims leaders move ~50% of their CAPEX across businesses over a decade. That suggests they keep reassessing where returns are best, and they move money accordingly.

3. Big investments (especially in downturns)

Data suggest that leaders in the top 20% of the industry spend approximately 1.7 times the median capital spending on sales.

“Big investments” mainly mean two things. It means being willing to invest in capabilities that change the long-term position of the business, such as R&D, capacity, and new business building. It also means acting when the cycle makes those investments cheaper.

This is where working capital discipline matters. It gives you the cash to invest when others have to pull back.

4. Productivity leadership

McKinsey frames productivity as something leaders operationalise. They point to levers like consolidation, automation, exiting weak units, improving sales productivity, and cutting overhead costs such as sales and administration.

The key is consistency. In cyclical businesses, productivity is what keeps the economics from falling apart when prices drop.

5. Product differentiation

This is often the most difficult step, because it can require letting go of what used to work.

McKinsey argues the best performers expand gross margin faster than peers by selling more differentiated offerings. That usually requires a clear view of where the market is going, and sometimes means improving or replacing older products before competitors force you to.

Differentiation is not branding. It is a real improvement in what the customer gets and what they are willing to pay for.

Agrifood companies can struggle here because many buyers are trained to view inputs as commodities. Changing that mindset often takes proof, service, and business models that price around outcomes.

What the BCG report says

McKinsey looks across 15 years. BCG looks closely at the recent five-year stretch.

BCG calls 2020 to 2024 a “mixed bag.” Some companies benefited early from record-high commodity prices, but growth did not always turn into strong shareholder returns.

The headline number: median TSR across the 38 companies analysed was 4% from 2020 to 2024. That is twice the 2% TSR from 2014 to 2018 in BCG’s previous analysis.

But BCG quickly contextualises that “improvement.” Agribusiness still lagged almost every other industrial sector in its comparison set, outperforming only 4 of 36 sectors.

So what happened?

Volatility was real, but the mechanism matters

BCG points to two major drivers of volatility. First, COVID-19 disrupted agriculture supply chains. Next, the war in Ukraine disrupted grain and natural gas supplies, spiking prices for some commodities and inputs, such as fertiliser.

They also add a third structural layer, which is rising variability in weather patterns and climate risks that affect the prices of commodities such as coffee, cocoa, and palm oil.

These shocks helped some companies, especially early in the period. For major row crops, the effects were strongest in the first half, then became more mixed as prices normalised.

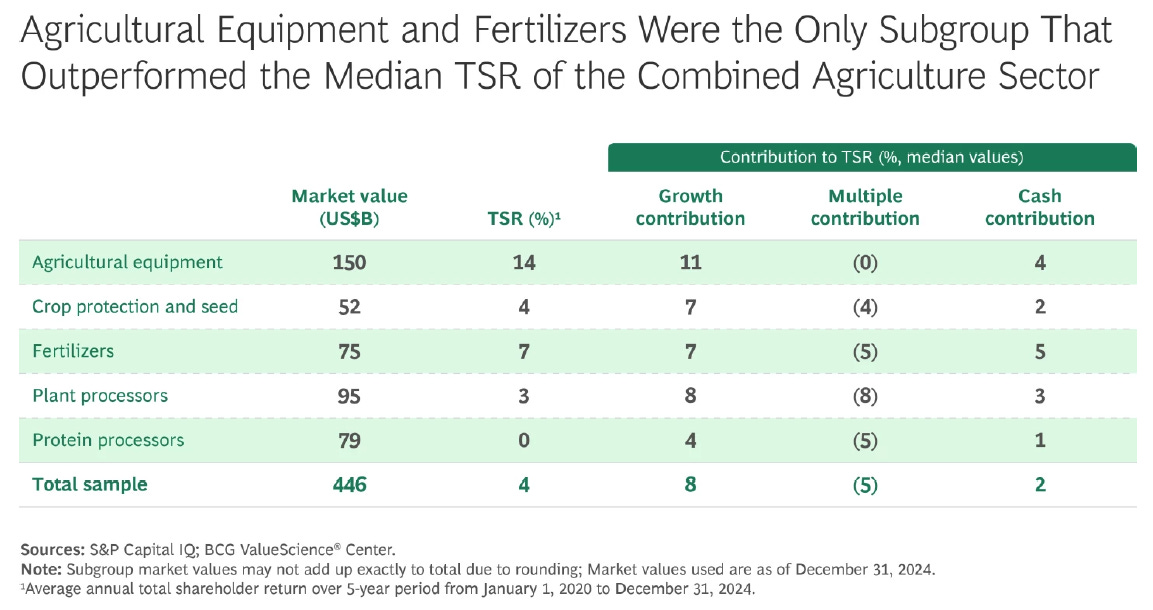

Growth happened, but valuations fell

Median revenue grew 8%. Margins and cash contribution rose slightly. But valuation multiples fell by 5% overall, with every subgroup contributing to the decline. A valuation multiple is the price investors are willing to pay for a company’s earnings. When multiples fall, it means the market is paying less for each dollar of profit.

So even though companies grew, investors did not reward that growth with higher valuations. Returns stayed modest.

This is typical in cyclical industries because growth and valuations often move in opposite directions. Investors tend to “price in” expected cyclical movements based on previous cycles.

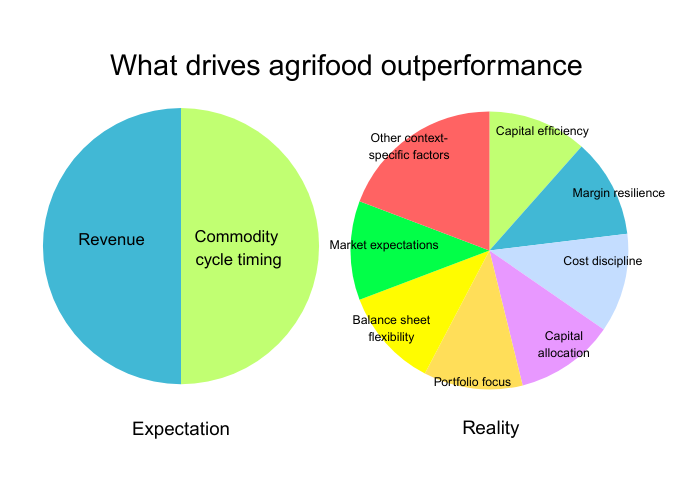

The implication is important. You can’t rely on growth alone to drive returns. If the market believes your growth is mostly cyclical, it will treat it that way.

What you need is a mix of levers that are credible even when the cycle turns. Margin resilience, cost discipline, balance sheet flexibility, and a clear story about why your earnings power is structurally improving.

Where value was created

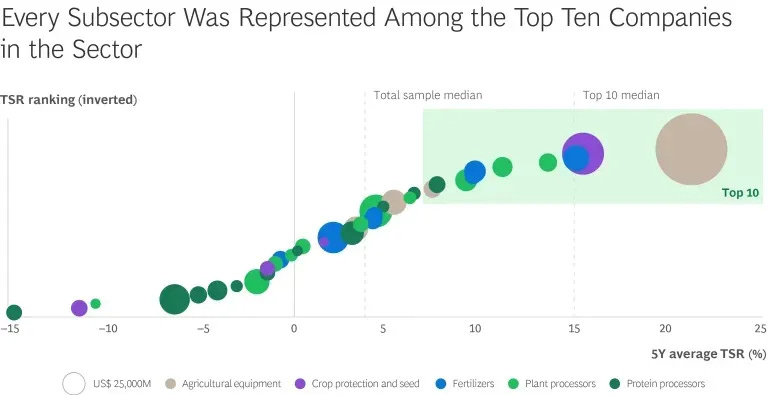

BCG splits the sector into five subsectors: agricultural equipment, crop protection and seeds, fertilisers, plant processors, and protein processors. The same shocks played out differently depending on where a company sat in the value chain.

Agricultural equipment led in value creation. BCG notes major players used M&A and joint ventures to upgrade capabilities. Even as unit volumes declined after the 2022 peak, higher prices linked to new technologies supported growth and returns.

In crop protection and seeds, performance diverged. A seed company (KWS) performed well due to margin and revenue growth. Corteva benefited mainly from seeds. Pure-play crop protection companies struggled later in the period as channel inventories were high and raw material supply was abundant, which pushed pricing down.

BCG also notes that large M&A deals in seeds and crop protection have had mixed results, which has pushed some companies to rethink portfolios and move toward simpler, more focused structures.

In fertilisers, BCG notes manufacturers generated the second-highest TSR. BCG cites CF Industries benefiting from lower natural gas prices in the US than in Europe.

In plant processors, results depended on product mix and geography. Ingredient-focused companies did better than commodity processors, partly because exposure to consumer pricing helped offset cyclical swings.

In protein processors, demand grew, but high feed costs limited gains. Higher TSR depended on cost control. BCG also notes growth in seafood processors, with Norwegian salmon companies benefiting from strong demand.

What separated the top value creators

The top ten performers delivered a median TSR of 15%, and every subsector had at least one standout. Growth was the largest driver, but the best performers were able to create value through more than one route, and to some degree offset the usual pattern where strong growth comes with falling valuation multiples.

BCG also points to common traits: market leadership in their subsectors, focus on core business, and aggressive cost and margin management.

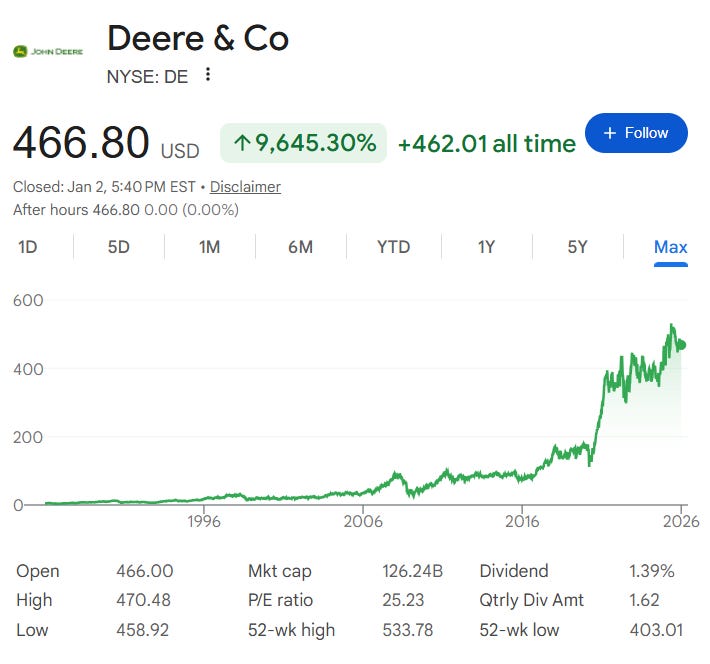

Deere stands out. From 2020 to 2024, Deere delivered ~21% per year in shareholder returns. Revenue and margin growth mattered, but Deere was also the only company among the top ten whose valuation multiple increased, and the only company in the full sample that improved across every TSR dimension BCG measured.

BCG attributes part of Deere’s performance to “smart industrial strategy,” and notes it was on track to meet or exceed 2026 targets for connected machines and digital engagement.

The winners “stack” advantages that defy the cycle

McKinsey and BCG are looking at different time horizons, but they are converging on the same meta-lesson. In agrifood, outperformance isn’t about “outguessing the cycle”. It’s about building an operating system that compounds through volatility and earns the right to invest when others pull back.

Here are the three takeaways that stood out to me:

1. Capital efficiency is the real differentiator

In a cyclical sector, capital efficiency is your primary source of optionality. When the cash conversion cycle drifts out by 30 days, you lose flexibility exactly when flexibility is most valuable. The winners treat capital turns as a strategic weapon.

By maintaining control of inventory and unpaid invoices and using assets efficiently, they keep cash available. That cash can fund productivity work, R&D, and selective acquisitions when competitors are playing defence.

2. Growth without structural change is a valuation trap

BCG’s data is a useful reality check: revenue can grow while valuation multiples compress, leaving TSR mediocre. That’s the cyclicality tax. If markets believe growth is just a price wave, they discount it.

To earn a higher valuation, companies need to show that profits are improving for structural reasons. In practice, that means stacking three levers: margin resilience (real differentiation customers will pay for), cost discipline (repeatable productivity), and balance sheet agility (working capital as a core competency).

3. The operating system is a set of repeatable behaviours

McKinsey’s “five big moves” are habits: doing regular, smaller M&A instead of one giant bet, shifting investment away from legacy businesses when returns fade, and investing through downturns rather than waiting for certainty.

Across subsectors, the consistent winners behave like rational capital allocators under stress. They shift from being price-takers in a commodity market to value-makers by continually re-shaping where they play and how they win.

Interested in more Better Bioeconomy content? I’ve been running an agrifood investor interview series, with conversations featuring investors from PeakBridge, Big Idea Ventures, Ajinomoto Group Ventures, and more. More to come in 2026!

If you found value in this newsletter, consider sharing it with a friend who might benefit from it! Or, if someone forwarded this to you, consider subscribing.

Thanks Eshan very much for excellent issue #131. There's so much to unpack here. A lot of these stats are over my head but the average consumer wants value low cost items like those prices at dollar stores and Wal-Mart. We need some major breakthroughs to produce really low cost alt protein that is a better value than traditional protein sources. That's where I'm hopeful that some company using AI will discover a way to produce lots of product for less. You created a very good AI issue and let's see if the data you mention on #131 will benefit from the exponential power of AI. That's when we'll see speculative traders really get on board with more and more alt protein companies, because these speculators are greedy. 2026 will see many positive developments in the space because we need it to happen. Necessity is the Mother of Invention. Thank you Eshan for all your help in educating us about some of the latest developments in this arena. May only good things come to you this year 👍♥️

Nice article. Happy new year